The Autonomy of Paper

Price transparency, comparison shopping, delivery convenience, and status updates are status quo in e-commerce. Why can’t we have these things in prescriptions?

As a 90’s kid, I remember an era of paper-saving, pro-recycling propaganda displayed around the halls of grade school. Apparently the world was running out of trees, and therefore paper, so it was generally thought that reducing the global consumption of paper was the answer to saving the trees [1]. There were paper drives, instructional posters on recycling, the Three R’s of waste management (reduce-reuse-recycle), double-sided printing was a hard-fast rule, and teachers kept bins of gently-used palimpsestic sheets on reserve, for other less critical use cases.

Take It Back Foundation. Where to begin…

I also distinctly remember my first home computer—it shipped with a CD-ROM of Britannica’s Encyclopedia, the first and now obsolesced digitized encyclopedia [2], which I proceeded to print out in it’s entirety. This was arguably the beginning of the digital era, when only 36.6% of homes had a personal computer [3], a figure that would grow rapidly over the next two decades. We weren’t quite yet comfortable with our digital objects being digitally native, so the computer age apparently fueled paper usage for some time [4]. Without smart phones, there was a tendency to print everything out — in all fairness, to use MapQuest on a roadtrip, you had to print out a stack of paginated and collated directions.

Fast-forward a few decades, and the paper crisis has vanished—a host of drivers have pushed us into a reality where paper usage has seemingly plummeted. Anecdotally, this is attributed to the ubiquitous rise of personal computers, cell phones, tablets, and e-readers. These gave way to e-mail, text messaging, the worldwide web and eventually the digitization of government, bank, and hospital records. Which brings us to prescriptions—and a practically bygone era of chicken-scratched medication data on templated pads of adhesive bound paper, marked by the iconic Rx ligature.

Although the global migration to a digital ecosystem seems like a natural progression in retrospect, the acceptance of electronic prescribing appears not to be a coevolution to the broader adoption of digital technology. While doctors are sometimes seen as early adopters, in reality the widespread use of e-prescribing is more likely attributed to a series of legislative acts that directly incentivized physician practices to migrate from paper prescriptions to digital prescriptions (e-Rx).

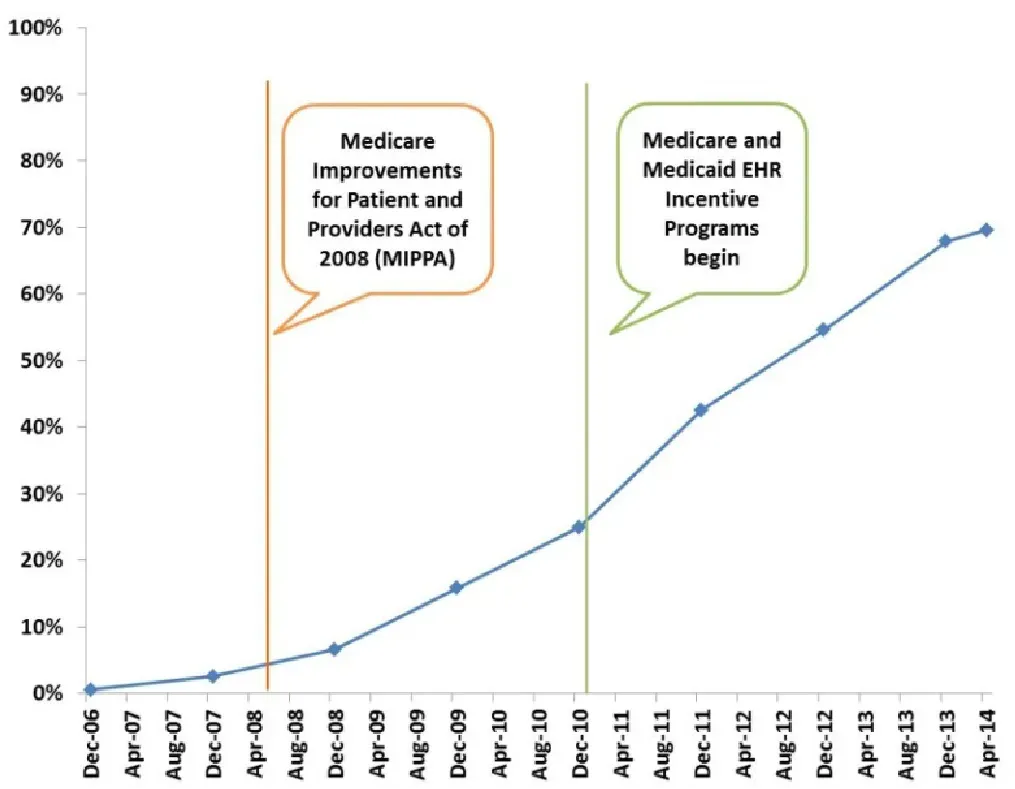

The rise of digital prescriptions arguably began in 2003 with the passing of Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA), which directly incentivized physicians to utilize e-prescribing, especially those participating in Medicare programs, offering up grants and reimbursements for software and hardware implementation as well as training and education for staff [7]. Beyond this, there was the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA) in 2008, which provided bonus payments for early-adopters and penalties for laggards [8].

While I won’t spend too much time in this article on the motivations of the United States government to incentivize the use of e-prescriptions, the apparent benefits of electronic prescribing are clear. Faster transmission, greater legibility and therefore accuracy (sorry, chicken-scratch), higher standards of patient safety, and workflow efficiencies. From the mouth of then Director of E-Health Standards and Services for CMS, Tony Trenkle, in an address to the Senate Judiciary Committee, e-prescribing had the potential to reduce overall drug spend (this can have varying definitions, but generally the total amount we collectively spend on prescription medications [10]) by “promoting appropriate drug usage” [11].

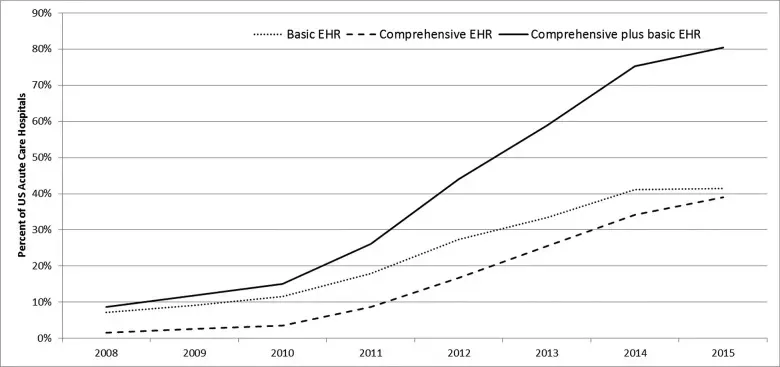

Up until this point, the usage of e-prescribing had actually been minimal, in spite of previous legislation—in December of 2008, only 7% of physicians were electronically prescribing through an EHR (Electronic Health Record) [9]. The issue was more rooted in the fact that widespread adoption of EHR software was lagging, which also meant data standards were inconsistent across different hospital and clinic settings—in 2008, less than 10% of Acute Care Hospitals were using EHR software [12].

And so we arrive at a seemingly simple question, how does a physician electronically prescribe? At the time of MIPPA, most practice and patient records were still being stored on paper in filing cabinets. Saving interoperability (the ability for different computer systems to communicate with one another) for another article, it was painfully difficult to transfer medical records between clinics and hospitals, let alone send a prescription to a pharmacy electronically.

HITECH fundamentally changed this, specifically incentivizing physicians and practices through the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs to adopt a certified EHR with electronic prescribing technology baked-in [13]. Twofer. By 2014, 70% of physicians in the United States were prescribing directly through EHR software, specifically through one third-party vendor, SureScripts [12]. At last, the powers that be achieved their goals of streamlining data and communication between healthcare providers, pharmacies and payors (ahem, insurance companies).

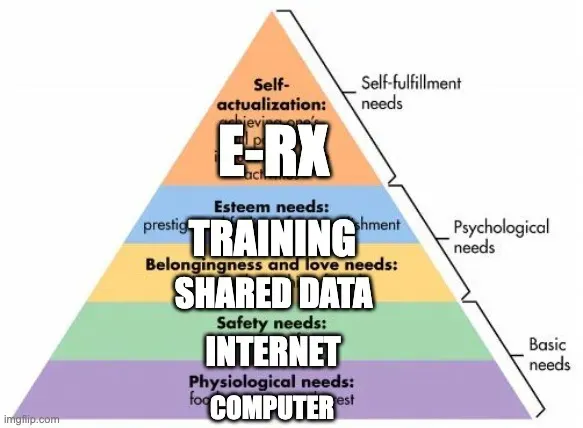

Well, what has been lost in the migration from paper to e-prescriptions? The mostly-uncited limitations enumerated in the Wikipedia on Electronic Prescribing are focused around friction for provider adoption (ROI, change management). Beyond those, it reads like the bottom two rungs of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs for technology (hardware, software, errors, data input, system downtime, security). Finally, it lists “patient access lost” whereas a patient can no longer request a paper prescription to physically take to a pharmacy (there are exceptions on a state-by-state basis), but misses the boat on why that actually matters.

Fast-forward to the rise of telehealth practices offering e-commerce: Keeps, Ro, Hims, and a slew of others to treat patient populations ranging from male pattern baldness to family medicine. Over the last 5 or so years, we’ve seen the rise of telemedicine and virtual care, greatly accelerated almost entirely by the immediate realities of the COVID-19 pandemic. Standards of care changed overnight, with many patients expecting telemedicine visits as an alternative to in-person visits, especially while traveling, though providers are sometimes reluctant (or maybe not as technology-forward as we thought) [14].

By one study of physicians in a New England health care system, “94% [of physicians in the study] transitioned to include virtual health care in their practice by December 2020,” [15]. Obviously, if you can’t leave your house as readily, virtual care is the clear alternative, so consumer demand drove shifts in an otherwise slow-going evolution to digital medicine.

To a certain extent, telemedicine solved a byproduct of the Great Pandemic Migration—millennials temporarily living at their parents’ house, families already on the verge of urban flight abandoning the city but needing access to care, and a general push for care in the comfort of your own home. Post-pandemic (can we say that yet?) realities have also shifted expectations for travel and work, leading to folks working from all over the country. Anyone caught traveling while in need of a prescription refill knows the pain of having to call both pharmacies or a physician’s office to have them transfer a prescription.

Flashing back to the 90’s again, there once was a world where the patient had agency in the ownership of their own prescriptions. A patient could price shop, they could take a prescription to their pharmacy of choice or on a whim, to a different pharmacy, without having to know at the point of prescribe in a doctor’s office. The rise of telemedicine has exposed fundamental gaps in the current prescription network — consumer expectations in e-commerce settings have trickled into healthcare settings. Price transparency, comparison shopping, delivery convenience, and status updates are status quo. The question becomes, why can’t we have these things?

- Gomez, J. M. (1991, March 15). Paper drives: Suddenly, they’re old news : Environment: The recycling craze has driven down the value of old newspapers and, ironically, has forced some groups to find alternatives to the fund-raising tradition. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-03-15-vw-405-story.html

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Britannica in the Digital Era. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Encyclopaedia-Britannica-English-language-reference-work/Britannica-in-the-digital-era

- Alsop, T. (2020, May 12). U.S. households with PC/computer at home 2016. Statista. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/214641/household-adoption-rate-of-computer-in-the-us-since-1997/#:~:text=The%20statistic%20shows%20the%20percentage,had%20a%20computer%20at%20home.

- Lewis, P. H. (1992, May 12). Learning to save trees. The New York Times. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/1992/05/12/science/personal-computers-learning-to-save-trees.html

- Virginia Commonwealth University. (1925). Prescription Pad. VCU Libraries Digital Collections. photograph, Richmond, VA. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://digital.library.vcu.edu/islandora/object/vcu%3A6535.

- Sacco, A. (2009). BlackBerry Curve 8330 with Stethoscope. CIO. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.cio.com/article/278205/blackberry-phone-dr-blackberry-eight-apps-making-medicine-more-mobile.html.

- Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, H.R. 1, 108th Cong. (2003). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-108publ173/pdf/PLAW-108publ173.pdf

- LeMasurier, J. D., & Edgar, B. (2009, April). MIPPA: First broad changes to medicare part D plan operations. American health & drug benefits. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4106553/

- Gabriel, M. H. (2014, July). E-Prescribing Trends in the United States. HealthIT.gov. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/oncdatabriefe-prescribingincreases2014.pdf

- Prescription drug spending. U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.gao.gov/prescription-drug-spending

- Trenkle, T. (2012, April 7). Testimony of Tony Trenkle. Committee on the Judiciary. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Trenkle%20Testimony%20120407.pdf

- Adler-Milstein, J., Holmgren, A. J., Kralovec, P., Worzala, C., Searcy, T., & Patel, V. (2017). Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: the emergence of a digital “advanced use” divide. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA, 24(6), 1142–1148. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocx080

- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Title XII: Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH), H.R. 1, 111 Cong. (2009). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ5/pdf/PLAW-111publ5.pdf

- Cordina, J., Fowkes, J., Malani, R., & Medford-Davis, L. (2022, August 4). Patients love Telehealth — physicians are not so sure. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/patients-love-telehealth-physicians-are-not-so-sure

- Kori S. Zachrison, M. D. (2021, December 30). Physician characteristics associated with early adoption of virtual health care. JAMA Network Open. Retrieved May 13, 2022, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2787595